Cosmetic Use and Dry Eye

By Laura M. Periman, MD, Leslie E. O’Dell, OD, FAAO & Amy Gallant Sullivan, BS

According to market research, roughly 66% of women regularly use eye makeup,1 particularly eyeliner and mascara, which are applied within close proximity to the meibomian glands and ocular surface. Other commonly used cosmetics include creams, concealers, and eye shadows that are applied directly onto the eyelids and can be absorbed into the delicate eyelid skin or flake into the eye and tear film. Furthermore, makeup removers are often used around the eye, where they can leach into the tear film. Many of these types of products are toxic to the human ocular surface and adnexal cells.2

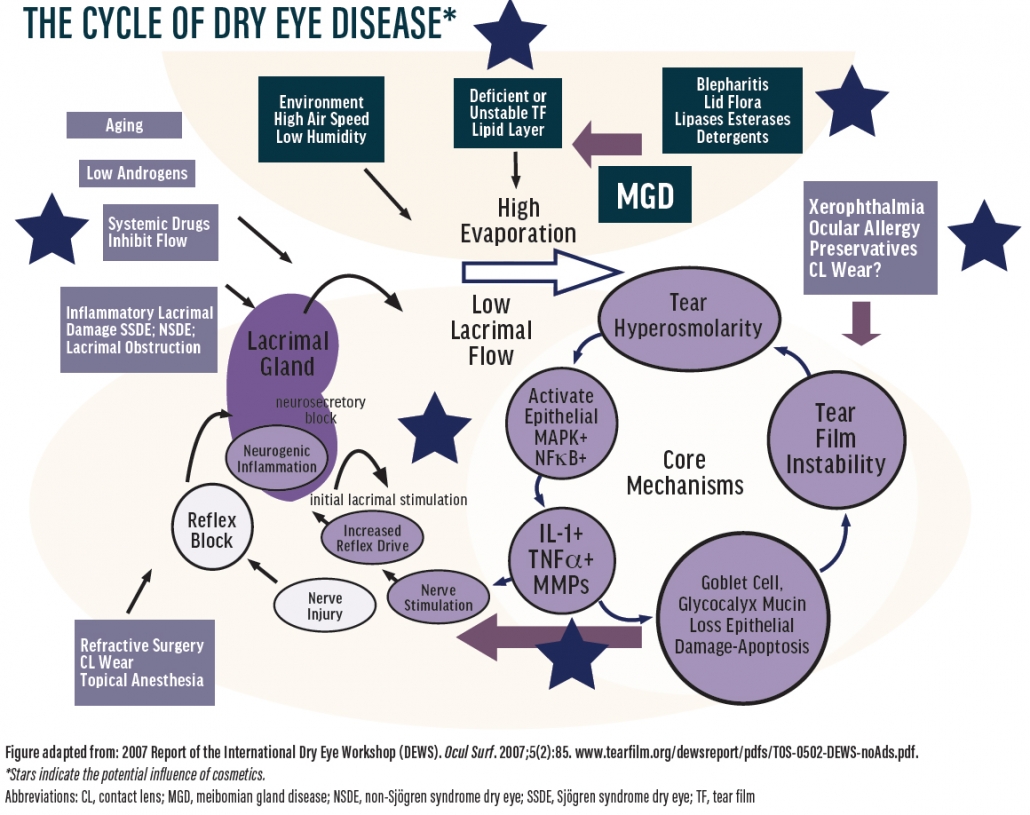

Every eye care provider should be well versed in the beauty practices of his or her patients, as the suspected correlation between eye health and makeup use (see The Cycle of Dry Eye Disease) is on the rise. Remember, the laws that govern the cosmetic industry are 81 years old, established in 1938 by the Food, Drug, and Cosmetic Act.3 It’s also important to note that the men’s beauty market has grown and is considered to be among the best performing segments of the personal care industry.4 Below is a brief rundown of the many ways that cosmetic use can contribute to dry eye and related conditions.

THREATS TO THE OCULAR SURFACE

Application of cosmetics to the eye can contribute to corneal nerve irritation, dendritic cell activation, hyperosmolarity of the tear film, meibomian gland dysfunction, and tear film instability, along with symptoms of dry eye.5 The eyelid margin is an area of great concern with regard to overall tear film stability and ocular health, yet current beauty trends recommend that this is the perfect place to apply eyeliner.

Most patients are unaware that the eyelid margins contain the meibomian gland terminal ductules, which are important oil gland openings for delivering protective oils to the tear film. However, trending makeup application techniques such as waterlining or tightlining often block meibomian gland orifices and introduce chemicals that may interfere with ocular health. Eyeliner applied on the inner portion of the lash line has been shown to migrate into the eye 15% to 30% of the time.6 Patient education is paramount in changing this ubiquitous and harmful beauty trend.

Other aspects of eye makeup, such as estrogenic active ingredients and toxic preservatives, can contribute to localized endocrine modulation and result in a phenotypic dysregulation of the meibomian glands and the epithelia that are necessary for producing quality tears.

Another omnipresent ocular surface threat is the recent obsession with long eyelashes. In reality, unnaturally long eyelashes pose a risk for dry eye disease. Normal eyelash length is one-third of the width of the eye opening, enabling optimized ocular surface protection from allergens, dust, debris, and air flow.7 When the lashes are abnormally lengthened, this important protective mechanism is lost.

BLEPHARITIS

Eye makeup can throw eye care providers off during an examination. Eyeliner, mascara, and eye shadow can mask or mimic blepharitis. Eyelashes covered in mascara can mask evidence of Demodex infestation.8 Eyeliner on the lid margin can mask evidence of ocular rosacea (telangiectasias) and mask meibomian fluid abnormality or gland dysfunction.

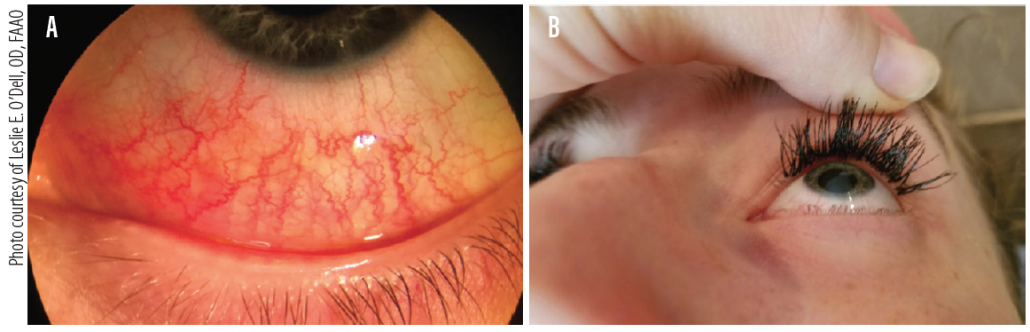

Use of false eyelashes is yet another area of concern. The glue used to adhere the false lash to the existing lash has been associated with contact dermatitis, allergic reactions, and inflammation that can exacerbate blepharitis (Figure 1). Also, proper lid cleaning is often not performed by people with false lashes due to a fear of lash loss, leaving a breeding ground for bacteria, fungus, and even Demodex.

Figure 1. Marked allergic and chemical conjunctivitis (A) after improper application of eyelash extensions applied to superior line of Marx (B) one day prior, blocking meibomian glands. This patient had to have the false lashes removed immediately due to her severe ocular symptoms.

ALLERGY AND INFLAMMATION

Eyelash adhesives are cyanoacrylate- like adhesives that often contain methacrylates, volatile organic compounds, and the well-known preservative and ocular irritant formaldehyde.9 The chemical cocktails used in many ocular cosmetics add to the risk of allergy for our patients, often presenting as contact or atopic dermatitis. Additionally, these chemicals can leach into the ocular surface during application, creating a chemical conjunctivitis or chemical keratitis (Figure 2). Even nail polish and acrylic fingernails can cause chronic dermatitis in patients because many contain high levels of volatile organic compounds and formaldehyde.

Figure 2. This patient presented with significant blepharitis and complaints of dry eye 2 weeks after application of eyelash extensions. The patient admitted to discontinuing eyelid hygiene to prevent damage to the extensions.

Complications of skin and eye products can also be related to allergy or toxicity. Creams and cosmetics used in beauty routines are often applied around the eyes, and vitamin A, retinoids, and parabens present in these formulations can have negative effects. These ingredients have been shown to cause significant toxicity to human meibomian gland cells in culture,10 and this is suspected to contribute to meibomian gland dysfunction and atrophy, and therefore potentially to dry eye disease.11

Eyelash tinting and dyeing has been associated with severe conjunctival reactions, swelling, watering, and acute inflammation secondary to chemical toxicities and allergic reactions to the chemicals and dyes used around the eyes.12,13 Additionally, hydroxycinnamates, a class of aromatic acids or phenylpropanoids, are phytochemical (plant-based) oils known to directly activate transient receptor potential channels on nerves and immune cells, which may result in upregulation of proinflammatory cytokines IL-1B, IL-4, and IL-16, and neurotransmitters involved in pain and itch signaling.14

ISSUES SPECIFIC TO CONTACT LENS WEARERS

Mascara can be mechanically and chemically irritating if it flakes into the tear film. For contact lens wearers, these flakes can become trapped under a lens, causing corneal erosion.15 Many pigments used in eye makeup are nondissolving, and hard particulates can become lodged under a contact lens and scratch an unprotected ocular surface.

BUYER and CLINICIAN BEWARE

Our patients’ beauty practices can wreak havoc on the ocular surface, and labels such as plant-based, natural, organic, vegan, and ophthalmologist-tested do not equate to ocular surface safety. Eye care practitioners need to be aware of the potential adverse effects associated with the use of eye cosmetics and antiaging products. Educate yourself about the latest trends, and discuss beauty routines with your patients, regardless of their gender. For information on beauty blunders, chemicals to avoid, and beauty habits to recommend, visit dryeyediva.com.

1. Frequency of makeup use among consumers in the United States as of May 2017, by age group. Statista. www.statista.com/statistics/713178/makeup-use-frequency-by-age/. Accessed April 23, 2019.

2. Chen X, Sullivan DA, Sullivan AG, et al. Toxicity of cosmetic preservatives on human ocular surface and adnexal cells. Exp Eye Res. 2018;170:188-197.

3. Federal Food, Drug, and Cosmetic Act (FD&C Act). US Food & Drug Administration. www.fda.gov/regulatoryinformation/lawsenforcedbyfda/federalfooddrugandcosmeticactfdcact/default.htm. Accessed April 8, 2019.

4. Men’s personal care market to reach $166 billion, globally, by 2022-Allied Market Research. PR Newswire. October 19, 2016. www.prnewswire.com/news-releases/mens-personal-care-market-to-reach-166-billion-globally-by-2022-allied-market-research-597595471.html. Accessed April 23, 2019.

5. Wang MT, Craig JP. Investigating the effect of eye cosmetics on the tear film: current insights. Clin Optom (Auckl). 2018;3:10-40.

6. Ng A, Evans K, North RV, Purslow C. Migration of cosmetic products into the tear film. Eye Contact Lens. 2015;41(5):304-309.

7. Amador GJ, Mao W, DeMercurio P, et al. Eyelashes divert airflow to protect the eye. J R Soc Interface. 2015;12(105). pii: 20141294.

8. Buckley, RJ. Time to wake up to make-up. Ophthalmic Physiol Opt. 2012;32(6):443-445.

9. O’Dell LE, Sullivan AG, Periman LM. Beauty does not have to hurt. Advanced Ocular Care. 2016;July/August:42-47.

10. Epstein SP, Ahdoot M, Marcus E, Asbell PA. Comparative toxicity of preservatives on immortalized corneal and conjunctival epithelial cells. J Ocul Pharmacol Ther. 2009;25(2):113-119.

11. Ding J, Kam WR, Dieckow J, Sullivan DA. The influence of 13-cis retinoic acid on human meibomian gland epithelial cells. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci. 2013;54(6):4341-4350.

12. Hansson C, Thorneby-Andersson K. Allergic contact dermatitis from 2-chloro-p phenylenediamine in a cream dye for eyelashes and eyebrows. Contact Dermatitis. 2001;45(4):235-236.

13. Kaiserman I. Severe allergic blepharoconjunctivitis induced by a dye for eyelashes and eyebrows. Ocul Immunol Inflamm. 2003;11(2):149-151.

14. Gouin O, L’Herondell K, Lebonvallet N, et al. TRPV1 and TRPA1 in cutaneous neurogenic and chronic inflammation: pro-inflammatory response induced by their activation and their sensitization. Protein Cell. 2017;8(9):644-661.

15. Uematsu M, Mohamed YH, Eguchi H, Imai S, Kitaoka T. Corneal erosion with pigments derived from a cosmetic contact lens: a case report. Eye Contact Lens. 2018;44(Suppl 1):S322-S325.